Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen: Baking EV Charging

⚖️ Navigating the Complex Standards Landscape of EVSE

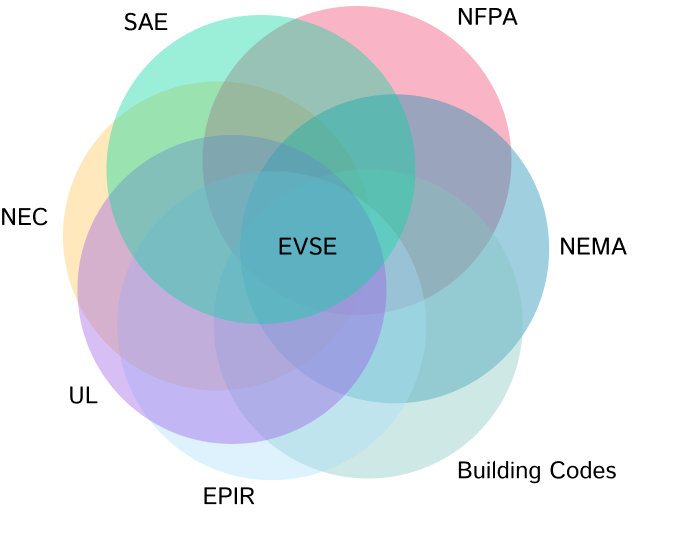

The biggest challenge facing EVSE innovation today is not a lack of technology, but rather the overwhelming number of agencies simultaneously attempting to regulate it. The adjacent Venn diagram illustrates this crowded space. Each organization serves a purpose, but when its standards conflict, overlap, or overreach, it introduces cost, delay, and sometimes even drives companies out of the U.S. market entirely.

NFPA 70 - National Electrical Code

While published by the National Electric Code (NEC), NFPA 70 is a "model code" that is then adopted by states, typically with minor changes each year. These changes take years or decades to trickle through, meaning that every state is essentially an Island with regard to codes. This means that EVSE standards imposed here create a wide range of adoption variations among states, further creating a burden on installation and operation for national distributors and companies looking to standardize and reduce costs. These increasingly complex changes add cost and confusion. Worse still, the NEC is positioning itself as the definitive authority on EV charging, which often shifts from safety concerns to political infrastructure relevance and away from product safety. Please start treating EVSE installations like the standard circuit they are.

Other NFPA Standards - National Fire Protection Association & Local Fire Codes

NFPA’s core mission is fire safety. That is valid and vital; however, their expanding influence over EVSE installation requirements includes energy power shutoffs and added signage. EVSEs are fundamentally electrical appliances, and their fire risk is not unique relative to other household or commercial electrical loads. NFPA should limit its oversight to fire-related design standards and defer to existing frameworks for electrical and automotive safety elsewhere. Prescribing power levels, communication protocols, or system architecture without deep domain knowledge risks confusion, cost inflation, and worse—stagnation. An example that stalled all charging installation in San Francisco last year was the city fire department requiring fire sprinkler upgrades for the installation of EVSE in parking garages from a 1.5gpm to 2.5 pgm, often requiring a new water main, and hundreds of thousands of dollars of new fire sprinklers to install $80-100k in charging.

SAE - Society of Automotive Engineers

SAE plays a critical and appropriate role in the EVSE space—defining plug formats, communication protocols, and vehicle-side interface standards. This is necessary. The EVSE’s primary function is to communicate safely and effectively with the vehicle. SAE’s leadership on ISO 15118 and related V2X protocols reflects its understanding of what vehicles need to function safely and reliably. This standardization helps ensure global compatibility while supporting long-term innovation and growth. SAE has a long-standing track record and established process for developing standards that promote interoperability among automotive companies, while also setting minimum safety requirements for vehicles when adopted by national homologation organizations.

UL - Underwriters Laboratories

UL is the anchor for safety at the device level. Its job is not to prescribe how EVSE should be designed, but to ensure that whatever is brought to market meets minimum safety and operational reliability thresholds—across leakage current, arcing, temperature, and more. UL’s standards strike an essential balance: enabling innovation while protecting users. UL 2231, UL 2594, and efforts like UL 1741 for V2X are examples of standards that evolve with the market, rather than trying to control them. While UL is not perfect, the process for defining and maintaining product-level safety standards is where EVSE safety should be determined.

Building Codes

Building codes, particularly those outlined in Title 24 and CALGreen in California, are increasingly mandating the readiness of electric vehicles (EVs). This can be beneficial, but it can also be hazardous if it is misaligned with the broader ecosystem. Building codes should not dictate how safety requirements are met or what qualifies as an EVSE or access to energy to charge cars; instead, they should rely on standards established by organizations such as UL or SAE for those definitions. These decisions need to remain flexible, focused on outcomes (readiness and access), and not prescriptive to specific power levels or technologies. They should treat EV charging as a black box and ensure the safety of the infrastructure downstream of any circuit, as well as precise safety requirements for construction.

Reach codes also touch EVSEs and often specify electrical details. For example, 40-amp circuit requirements add to excessive power budgets and added copper costs that will never be used.

The Federal Access Board (ADA)

As of this writing, guidelines have been established, but not national standards, for charging accessibility. Instead, it’s a state-by-state thing. However, docket ATBCB-2024-0001 will turn guidelines into rules. Some of these rules present barriers not to persons with disabilities, but to accessing charging facilities at all, making it impossible to retrofit charging into existing parking lots legally.

NEMA - National Electrical Manufacturers Association

NEMA represents manufacturers of electrical equipment and plays a significant role in shaping technical standards and code proposals, often influencing the language and interpretation of the National Electrical Code (NEC). In the EVSE space, NEMA’s members include companies with vested interests in traditional infrastructure and hardware-heavy solutions. While NEMA provides valuable insights into component safety and product interoperability, its advocacy sometimes reflects business models that favor large-scale, high-cost hardware deployments, which may be at odds with emerging lightweight or distributed charging solutions. When NEMA pushes for prescriptive hardware requirements or discourages flexible architectures, it risks entrenching legacy interests over market innovation. NEMA’s input must continue to focus on safety and interoperability, rather than using standards as a lever to preserve incumbent market positions.

EPIR - Incentive Programs

EPRI plays a supporting role in shaping how utilities and energy systems adapt to mass electrification, but has increasingly influenced funding eligibility through technical specifications. While their research into grid impacts is valuable, their involvement in incentive program criteria has led to prescriptive technology mandates, such as requiring OCPP 1.6, OCPP 2.0, or ISO 15118 for EVSE eligibility. These protocols have no bearing on safety and instead prescribe specific architectures for how chargers must communicate, often favoring one design approach over others without regard to cost, user needs, or deployment complexity. EPRI’s role should remain focused on grid readiness and infrastructure modeling, not narrowing the field of innovation through backdoor technology mandates embedded in public funding criteria.

💸 Incentive Programs and Political Prescription

A final, yet increasingly powerful, influence on the EVSE ecosystem comes from incentive programs—often created as political infrastructure by state and federal agencies with good intentions but poor technical alignment. Many of these programs now require features such as OCPP 1.6/2.0 or ISO 15118, minimum delivery (kW) requirements that require all ports to be able to deliver 100% all the time, ensuring the electrical system is vastly oversized to the actual needs for eligibility, regardless of project scale, customer use case, or economic viability. This prescriptive approach turns public investment into a rigid solution matrix, rather than leveraging the private sector’s creativity and technical depth. At their best, these programs should support outcomes—access to safe, cost-effective charging where vehicles are parked, not dictate the protocol or plug that delivers it.

🚧 The Real-World Implications

Many EV owners never install a wall-mounted Level 2 charger. They plug into a standard outlet or a NEMA 14-30 dryer plug with a mobile connector and charge their vehicle overnight just fine. When we start layering prescriptive GFCI requirements, power minimums, and V2X constraints into code or incentives, we risk outlawing cost-effective, user-friendly charging solutions that already work. The recent changes to 625.4 will push more homeowners to install outlets that they pretend are not for EVSE. Yet, hardwired EVSEs are easier to install correctly.

As the CEO of Orange, I’ve seen firsthand how conflicting requirements from these organizations slow innovation. Even when we meet safety standards, incentive programs, or fire code interpretations may add yet another layer of conflicting logic that disqualifies products like the Orange Outlet in favor of high-power wallboxes. That’s not progress—it’s calcification and stagnation of innovation.

🧩 Conclusion: A Call for Collaborative Restraint

Every agency in this diagram has a role to play—but no one agency should overstep its expertise. NEC, NFPA, UL, SAE, and local building code bodies must respect one another’s domains and align around a shared outcome: enabling scalable, safe, and affordable electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure.

The EVSE of the future will support not only charging but also grid integration, energy optimization, and resilient power. If we over-regulate today, we strangle that future before it arrives. Let’s allow innovation while ensuring logical, clear safety standards from organizations like UL and SAE, who have strong track records of evolving with industries vs stifling them.

Recent Writings

A Founder’s Reflection of 2025

By: Nicholas Johnson

A founder’s reflection on leaving Orange, the collapse and rebirth of energy markets, and why AI and infrastructure are entering a new phase in 2026.

Zero to One Through Great Customer Discovery

By: Nicholas Johnson

Over the last several months, I've been helping several other founders who are early or have had to pivot from their original idea. Each time I encounter the same friction or resistance from founders, I have been there myself, facing the pushback of talking with customers and asking

Three Quarters of Growth: What Orange Learned Building EV Charging for Multifamily

By: Nicholas Johnson

Context: A deep dive into Orange’s last three quarters—covering GTM execution, revenue growth, hardware challenges, and the unique dynamics of selling into multifamily properties. Focuses on business model design, utilization, connectivity, and why Orange’s approach is fundamentally different from traditional EVSE providers. Post Body: When we started